Community Actions and Innovations

Many schools and communities took creative action to support students commuting to school during the 2020-2021 school year. Managing in-person school re-openings with COVID-19 prevention measures brought forth a combination of innovations and renewed interest in long-standing strategies that could ultimately accelerate the uptake of safe school travel options and improve overall safety for the long-term.

“Walking school buses, bike trains, and new park and walk locations are being viewed as fresh options by some who had previously not considered regularly participating.”

– Massachusetts Safe Routes to School (SRTS) Outreach Coordinator

Actions and innovations highlighted here are responses to a call for examples of good practices during spring 2021. Schools, communities, and states across the country shared what they accomplished in support of a variety of transportation options while also implementing COVID-19 prevention measures. The actions and innovations include:

- Temporary infrastructure improvements

- Slow Streets/School Streets

- Expanded school walk zones

- Staggered dismissal times

- Park and Walk programs

- Quick-build and fast-tracked infrastructure improvements

- Opening of back school gates

- Promotion of active transportation

- Walking school buses

- Adjusted school bus schedules and seating

- School buses/transit for needed services

- Celebration of Walk and Bike to School Days

Temporary infrastructure improvements

Temporary infrastructure improvements, also called pop-up demonstrations and tactical urbanism, provide great opportunities for communities to try changes. Low-cost materials are used to implement short-term street design changes and collect community feedback. Common improvements include bike lanes, crosswalks, and curb extensions to shorten street crossing distance.

Example

Indianapolis Public Schools secured a “tactical urbanism” grant from the Indiana State Department of Health to trial safety improvements in front of Butler Lab School. During the pandemic they purchased pavement tape, paint, stencils, and signs to create their own crosswalk to serve the “walker” entrance (opposite the drivers) and had enough materials remaining to stripe demo bike lanes to connect to the greenway a quarter mile away. They are working with city government to make the changes permanent.

Indianapolis, IN/Butler Lab School

Los Angeles, CA/LA DOT Livable Streets

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the city of Los Angeles started using pop-up projects to help communities experience the recommended infrastructure included in school neighborhood improvement plans, which have been developed for the schools in the city with the greatest needs for improved safety conditions.

Resources

Massachusetts Safe Routes to School Pop-up Projects for Safe Routes to School: Explores how schools can use pop-up demonstration projects to improve safety on and around campus.

Los Angeles Department of Transportation Safe Routes to School Street Pop-up Events: Describes the major elements of pop-up events and displays videos of past events.

Slow Streets/School Streets

Closing or limiting access to a street that borders a school creates space for walking and biking. It also allows for more physical distancing when needed. Slow Streets place barriers on streets, closing one or more lanes to car traffic and reallocating to pedestrians and cyclists. Delivery, city service, and emergency vehicles and some local traffic are still permitted to pass through with caution and at lower speeds—usually only five to 15 miles per hour. The World Health Organization recommends that the speed of motorized traffic should be lower than 20 mph in areas where child pedestrians and bicyclists mix with motorists.

Street closures and slow streets would have been more challenging to implement before COVID-19, but now that places are experiencing it, many communities are considering making these changes permanent.

Examples

Begun during the pandemic, Seattle’s Stay Healthy Streets and School Streets in front of schools are open to people walking, rolling, and biking, and closed to pass-through vehicles. School Streets provide more space for social distancing at school pick-up and drop-off. Spanning one or two blocks directly next to schools, they are clearly marked with “street closed” signs which means that they are closed to all pass-through traffic.

Seattle, WA/Seattle DOT

San Francisco, CA/San Francisco Municipal Transit Agency

San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency is encouraging parents, students, and teachers heading back to the classroom to use their Slow Streets network as a good way to introduce children to walking and biking to school.

Somerville, MA has designated multiple streets across the city to be Shared Streets. With slower speeds and fewer cars, these residential streets are prioritized for bicyclists and pedestrians to navigate and maintain physical distance while making daily car-free trips to schools, grocery stores, and other essential locations.

Resources

Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center Re-envisioning School Streets: Creating More Space for Children and Families: Discusses street and school campus characteristics that influence opportunities to limit motor vehicle access to a street and presents case examples.

Minnesota Safe Routes to School: School Streets + Park and Walk: Describes how to combine street access changes and remote parking.

Expanded school walk zones

Expanded walk zones support active transportation while relieving pressure on bus services which may have limited capacity because of physical distancing requirements. Places are considering keeping expanded walk zones because of the benefits of providing an opportunity for healthy activity for students while reducing the number of vehicles on school campuses.

Example

Arlington County (VA) Public Schools expanded walk zones at 16 elementary schools to prepare for reduced busing capacity and to support walking to school. A Walk Zone Work Group developed considerations for walk zones based on safety needs. The team took several actions in advance of expanding the walk zones, including reallocating several crossing guards to support priority intersections, coordinating with Arlington County Police to monitor/support priority intersections as needed, adjusting signal timing and pedestrian countdown timing to allow more time for street crossings and eliminating the need for

pedestrian activation of crossings, new or enhanced school zone signage, deployment of variable messaging signs on busiest roadways near schools to attune drivers to the presence of students, and pedestrian flag deployment at unsupported crossings at intersections near schools. The team also conducted walk audits to develop maps and recommendations to support families/students residing in the newly expanded walk zones.

Staggered dismissal times

Staggering the times when students leave school by mode of travel (for example, first dismissing walkers and bicyclists, then bus riders, then car riders) can reduce congestion on and around campus, especially for students who are walking and biking. Allowing students who walk or bike to leave first is also an incentive to use active transportation.

Example

Campbell Middle School, Cobb County, GA, adjusted the dismissal time of students by mode of transportation, dismissing walkers first, then cyclists, and then car riders. Bus riders were dismissed last and were divided by grade level. Bus riders would either use the front or back hall to proceed to buses. This minimized the amount of foot traffic in any given hallway at any one time.

Park and Walk

Changing where drivers drop-off students can reduce congestion on school campuses. Park and Walk – or remote parking – allows children (accompanied by adults depending on the child’s age and route) to walk a short distance to school and helps to reduce morning congestion at the school. Usually, one or more sites within walking distance of a school (typically one-half mile) are designated places where families, and sometimes school buses, drop off students in the morning so they can walk the rest of the way to school, or park and walk with their students. Many places have been setting up “Park and Walk” programs in recent years while others are starting them now in response to COVID-19.

Examples

Bedford, MA/Bedford Public Schools

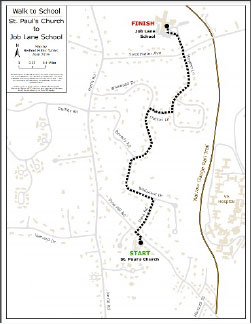

Bedford (MA) Public Schools created route maps for Walking School Buses and Bike Trains as well as Park and Walk locations to address increased car congestion at arrival and dismissal and to encourage more students to walk and bike. Middlesex Community College granted permission for students to use their parking lot near the Narrow Gauge Trail as a Park and Walk location to the Lane School. More students are walking and biking to the school by themselves, with parents, and in unchaperoned groups.

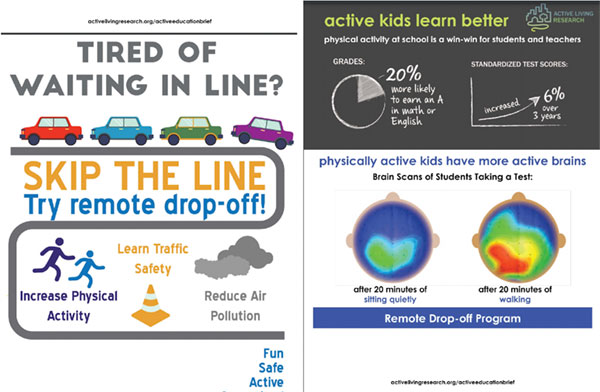

In North Carolina, a remote drop-off program that existed prior to COVID-19, the Piedmont Triad Remote Drop-off Program, provides a fun, safe, and active way for children to travel to and from school with adult supervision. Caregivers are encouraged to drop their children at a pre-determined nearby location and have them walk in a supervised group to school. The Remote Drop-off Program aims to reduce the number of idling vehicles in school zones, lower the amount of asthma-related absences, and encourage a safe, active, and healthy route to school.

Piedmont Triad, NC/Piedmont Triad Regional Council

Resources

Local Motion, VT Getting Students to School During Covid: The Basics: Provides information on planning and running walking school buses / bike trains and remote drop off with a focus on safety and effectiveness during COVID.

ChangeLab Solutions Get Out & Get Moving: Opportunities to Walk to School Through Remote Drop-off Programs: Overview of remote drop-off strategy, managing risk, and rural settings.

Minnesota Safe Routes to School: School Streets + Park and Walk: Describes how to combine street access changes and remote parking.

Boulder Valley School District Safe Routes to School Three Block Challenge: Presents a program that encourages students to walk three blocks.

Quick-build and fast-tracked infrastructure improvements

Quick-build infrastructure projects use low-cost measures to create improvements such as pedestrian bulb-outs or new bike lanes with paint and bollards. Most quick-build projects can go from conception to reality within months, unlike major capital projects that may take years to plan, design, bid, and construct. They are intended to be evaluated and reviewed within the initial 24 months of construction.

Fast-tracked infrastructure projects are improvements that are accelerated because special circumstances require quick action. At times, when a project is scheduled for completion in four or five years, the local entity may front the cost of the project to speed up the process.

Examples

Boston, MA/City of Boston

Massachusetts Shared Streets and Spaces Program, established in June 2020, was immediately popular with Massachusetts cities and towns. The program provided grants from $5,000 to $300,000 for quick-build improvements to sidewalks, curbs, streets, on-street parking spaces, and off-street parking lots in support of public health, safe mobility, and renewed commerce. Since it began, the Shared Streets and Spaces Grant Program has awarded a total of $26.4 million dollars to 161 municipalities and four transit authorities to implement 232 projects.

Milwaukee, WI was in the midst of holding community workshops to identify priorities for low-cost infrastructure safety improvements around eight public schools serving low-income and Black or Latinx families when the COVID pandemic started. To accommodate the need for physical distancing and avoid gathering indoors, public involvement was modified into community walk audits and conducted outside with great success. As part of the walk audits, staff used chalk paint to draw outlines of potential infrastructure improvements to demonstrate how the project budget could be used at each school. These efforts ensured that physical distancing requirements were met while continuing to include parents, students, school staff, and neighbors in making decisions about street changes. Over 300 participants in diverse neighborhoods gave input on the SRTS infrastructure projects.

Harrisonburg, VA/Eric King

Harrisonburg, VA had a sidewalk improvement fast-tracked due to COVID-19. A new sidewalk was built at Thomas Harrison Middle School for students who live in a nearby neighborhood without school bus service. The project had been considered pre-pandemic but never committed to, so the pandemic and the need to provide space for student walkers was the catalyst for its construction and the sidewalk is now being used by students.

Opening of back school gates

For schools with neighborhoods behind or on a side of the school, using alternate entry points for the school campus can help create physical distancing, encourage active travel, and reduce traffic congestion at drop-off. It may also offer additional options for off-campus parking locations for families who live too far to walk from home.

Fairwood, WA/Nancy Pullen-Seufert

Example

Ridgewood Elementary School in Fairwood, WA, designated a staff person to monitor student arrival at the back gate as was required for COVID-19 prevention procedures. This allowed families to walk from nearby neighborhoods or use the parking lot at a park across the street, instead of requiring all foot and vehicle traffic to use the single entrance at the front of the school.

Promotion of active transportation

Encouraging active transportation takes many forms and has many benefits. Promotion includes providing walking and bicycling safety education, creating awareness of the need for physical activity, using events to encourage trying the activity, incentivizing active travel and holding virtual group walks or bike rides during times of in-home learning. Promotion is often supported by safety improvements including creating safer space for walking and bicycling and slowing the speed of cars.

Examples

Palo Alto, CA used transportation safety education to elevate transportation equity and remind parents and the community that cars were “not personal protective equipment.” Promoting active transportation is part of the Health Element under Santa Clara County’s (SCC) General Plan adopted in 2015 and is recommended through SCC’s Public Health Order for COVID-19. Their message is that active transportation supports the CDC’s efforts to promote one hour of daily exercise recommended for children, which results in improved concentration and academic performance and is vital for student physical, mental, and emotional well-being. Reducing traffic congestion around schools creates safer street conditions, provides better access for buses, and reduces idling and air pollution such as CO2 emissions that contribute to climate change. Commute options include Park and Walk locations and volunteer-based walking school buses and bike trains.

Alexandria, VA/Alexandria Safe Routes to School

The Minnesota Safe Routes to School Program encouraged active travel by developing a website to support student walking and biking in response to COVID. It covers a variety of topics, including park and walk, street closures, and how to lead walking school buses.

Promotional material in Alexandria, Virginia asks, “Why walk?” and gives reasons why it is a good idea.

Milwaukee, WI/Wisconsin Bike Fed

In Milwaukee, WI, the Wisconsin Bike Fed (WBF), a statewide bicycle advocacy group, re-tooled many of its SRTS program elements into a “Safe Routes from Home” curriculum and made it compatible for school district-supplied student computers. They began a new model of “Champion Training” in which WBF instructors met school staff at their houses to tailor a riding experience for them and/or their family to their school site. One teacher took her students on weekly rides even when they were learning from home.

Arizona encouraged continued physical activity for Tribal children through virtual walk to school events. After years of conducting in-person Walk to School events around Coconino County, AZ, the Navajo and Hopi Nations conducted a virtual Walk to School event in September 2020. Students and staff at all three sites participated in the virtual event by walking at least one mile per day from Sept 28-30th and emailing their teachers with the information. Tuba City Regional Health Care Corporation, the local SNAP-Ed coordinator, and local schools are making plans to embed this activity (in-person or virtual) into the Local Wellness Policies in each school or district so that active transport to school is a sustainable activity in future years.

Cobb County, GA/Campbell Middle School

Davis, CA, encouraged active travel by giving each elementary school bike/ped coordinator a Chromebook and scanner to scan Active4.me bar code tags of students who were walking and biking. Active4.me is a website using bar code tag scans to send text or email to parents notifying them their students have arrived at school.

In Cobb County, GA, chalk was used as a temporary infrastructure improvement to create student friendly crosswalks and sidewalks for Walk’N’Roll to School Day.

Walking school buses

Walking school buses are groups of students supervised by one or more adults walking the route to school. It can be as informal as two families taking turns walking their children to school to structured events with route meeting points, a timetable, and a regularly rotated schedule of trained volunteers. A variation on the walking school bus is the bicycle train, in which adults supervise children riding their bikes to school.

Communities have been using walking school buses and bicycle trains for several years, but they have been given a fresh look as part of pandemic response.

Example

The SRTS program in Marin County, CA initiated PedPods which encourages a few families with students in the same grade to walk together while maintaining physical distance. The idea is to keep the same “exposure circle” as the students have in class while supporting parents in trading off the responsibility of accompanying students. This adult supervision is also a way that parents whose schedules permit walking to school can help families who cannot do so.

Resources

The National Center for Safe Routes to School guide for starting a walking school bus

The National Center for Safe Routes to School guide for setting up bicycle trains.

Local Motion, VT Getting Students to School During COVID: The Basics describes walking school buses, bike trains and remote park and walk strategies with a focus on safety and effectiveness during COVID.

Adjusted school bus schedules and seating

During the pandemic, schools made adjustments to student dismissal times for school bus transportation and the school bus loading and unloading process This was done to limit exposure by minimizing congestion on the school campus and in the hallways of the school building.

Example

As part of its COVID-19 prevention measures, Campbell Middle School in Cobb County, GA adjusted the dismissal schedule of students by mode of transportation such as walkers, cyclists, and then car riders. The bus riders, depending on grade level, would either use the front or back hall to dismiss to buses. This minimized the amount of foot traffic in any given hallway at any one time.

The bus dismissal and arrival were also coordinated with where the students sat on the bus. The students sat by grade level on the bus with the 8th graders sitting up front, then 7th in the middle and 6th graders in the back of the bus. This allowed the 8th graders to exit the bus first upon arrival and walk to the other side of campus to their grade level area. The next group were the 7th graders who are housed in the central part of the campus. The last group to disembark were the 6th graders whose classes were the first few hallways. For dismissal, the order was reversed, allowing 6th graders to dismiss first and board first in the back of the bus, then 7th, then 8th graders.

School buses/transit providing needed services

When buses were not used for transportation during the height of the pandemic, some places used them to transport students to school virtually. Springfield, OR; Pierce County, WA; and the State of Louisiana reported using buses as Wi-Fi hotspots in neighborhoods. Sacramento Regional Transit also provided Wi-Fi hotspots.

Some places encouraged transit use by providing free bus fares such as in Charlevoix, MI.

Celebration of Walk and Bike to School Days

Walk to School Day 2020

While most schools operated remotely for much of the last year, schools and families still celebrated Bike to School Day and Walk to School Day in their neighborhoods. A survey of 2020 participants reflected celebrations in 44 states and DC. While events looked different than past years, participants said they used the day to unite around the same common goals as always, with community connection, physical activity and road safety rising to the top.

This fall Walk to School Day is set for October 6, 2021 and will be used as an opportunity to celebrate walking and biking as part of school re-opening.

Examples

In Keizer, OR, the Physical Education teacher brought his bike into the school neighborhood and took video of himself riding every route that leads to the school grounds. He put this video to music and sent it out to all students, staff and families and encouraged them all to go for a ride to the school or around their own neighborhood.

Yadkinville, NC/Michael Dorman

In Elgin, IL, students walked to school after the remote learning portion of the day and picked up a neighborhood bingo card. After the pick-up, they looked for various things on the walk around school and walk home (stop sign, traffic signal, etc.) or completed certain activities (pick up a piece of garbage they saw on the walk).

In Yadkinville, NC, Physical Education teachers posted the interactive daily information provided for Bike to School week and let their students know that they would be biking around the school communities to say hello ‘from a distance.’

In Severna Park, MD, students were given the task to take a bike ride with a parent that would have been the equivalent distance of riding to school.

In La Grande, OR, the Bike to School Day Coordinator noted “people have been isolated and afraid to let their children take public or mass transportation. This event was important to show that there are many ways for students to get to school without the fear of them being in close contact with others.”

Resource

National Center for Safe Routes to School official site for Walk and Bike to School Days: Offers planning advice and national registration of events.

CONTRIBUTORS

The National Center for Safe Routes to School gratefully acknowledges the following contributors who shared their local practices with us.

Michael Anderson, Wisconsin Bike Fed, Milwaukee, WI

Mitchell Askew, Cobb County School District, Smyrna, GA

Dave Cowan, Minnesota Department of Transportation SRTS, St. Paul, MN

Judy Crocker, Massachusetts SRTS, Boston, MA

Michael Dorman, Yadkinville Elementary School, Yadkinville, NC

Gwen Froh, Marin SRTS, Marin County, CA

Rosie Mesterhazy, Palo Alto SRTS Program, Palo Alto, CA

Lauren Hassel, Arlington Public Schools, Arlington, VA

Michael Hygema, SRTS Butler Lab School, Indianapolis, IN

Landon Hilliard, Boulder Valley School District SRTS, Boulder, CA

Wendi Kallins, Marin SRTS, Marin County, CA

Erik King, Sentara Health SRTS Program, Harrisonburg, VA

Derek Krevat, Massachusetts Department of Transportation SRTS, Boston, MA

Ashley Rhead, Seattle Department of Transportation, Seattle, WA

Christal Waters, Davis, CA

Also thank you to:

Kelly Cornett, CDC, and her colleagues around the country who submitted responses through her.

The schools and communities whose information was shared from the Walk and Bike to School website:

Elgin, IL

Severna Park, MD

Yadkinville, NC

Keiser, OR

La Grande, OR